Ireland's Child Care Institutions during the 20th. Century. Fo'T: The most vivid and passionate stories - banished babies, cruel orphanages, old abuses of power - have concerned things that went unnoticed, or at least unarticulated, at the time. News has often had to be redefined, not as the latest sensation but as that which everybody knew all along yet could not say.

Tuesday, February 14, 2006

Sunday, February 05, 2006

Friday, February 03, 2006

Thursday, February 02, 2006

My memories of beatings, intimidation and fear

As the Sisters of Mercy made a public apology recently at the Commission of Inquiry into Child Abuse to those whose childhoods were spent in the St. Joseph’s Orphanage in Dundalk, one woman has spoken out on her years in the orphanage. The 57 year old nurse, who now lives in London, was placed in the orphanage when she was just six months old and remained there until she was sixteen. “My memories consist mainly of unhappiness, beatings, intimidation and fear,” says Fiona (not her real name), her voice still betraying the devastating effects of her experience. The beatings I received as a child were horrific, regular, on the most sensitive body parts, and for no reason at all. I was an innocent child, like my colleagues, but they found things to beat us for, like standing out of line. I witnessed other children beaten because they wet their bed or could not talk properly. A memory persists of a baby coming in and because she cried during the rosary from missing her mother, she was walloped across the face.”

She accepts that not all the nuns were guilty of abuse. “There were three or four nice nuns, but they were in the minority.” Fiona says that while the children grew accustomed to the physical abuse, they never forgot the emotional abuse. I was told from a very early age that my mother was a dirty woman and that’s why I was in the orphanage. We were the product of sex, we were evil,” she recalls. “The Nuns were supposed to be helping society, and should not have been frowning on anyone or abusing children. We were the victims but they made us feel like they were doing us a favour. They gave us no love, care or attention.”

As acknowledged by a representative of the Mercy order at the public inquiry, St. Joseph’s orphanage was an unsuitable building for children, with inadequate heating. Fiona has abiding memories of the children being sent outside in all weather, even the depths of winter. “Our clothing was totally inadequate and we would huddle together for warmth and then if the nuns saw you huddling up against a colleague, you’d get a wallop.” Even when they went to school in Realt na Mara, Fiona says the children from the orphanage were treated differently, and were “systematically picked on and beaten by most of the nuns. I can vividly recall some of the other children asking me ‘why do they keep on beating you?’ Those of us who were illegitimate got a rougher deal as the nuns were fully aware that we had no one to turn to. Yes, we took it all and said nothing, but who could we have told, who would listen to us, we were the nobodies of society.”

Fiona says her only good memories from childhood are of being taken out twice a year by local organisations. “They treated us as children and with kindness.”

She admits that things started to change slowly for the better when she was around fourteen, but by then her self-esteem was low and she had an inbuilt fear and mistrust of anyone in authority. “However, my two years at the Technical School were a safe haven during the day from the physical and emotional abuse.” When she turned sixteen, she had to leave the orphanage and went first to Dublin and then to London. “A lot of girls would have gone to work on farms, but I knew I didn’t want that as I had done enough rubbing and scrubbing and slavery in the orphanage. When I left Dundalk, I didn’t know where I was going or what I was going to do. I had no education, didn’t know the value of money and had no social skills.”

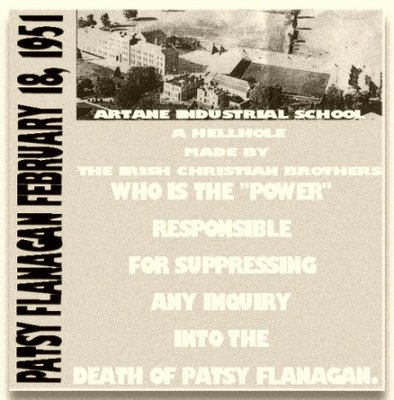

She has found that the best way to survive what she had experienced was to put it behind her, not to think about it. “When I was younger I wouldn’t let anyone know where I was from. I had no sense of identity, had no mother or father, brother or sisters, so I told lies, lots of lies, as I didn’t want to be humiliated ever again.” Fiona was determined to take control of her life from then on. “I had to strive and strive. I worked very very hard for what I got.” She qualified as a nurse, got married and raised a family. “I don’t want to live in the past. I’ve tried to put it behind me and I hope I have peace of mind.” She is, she believes, lucky to have carved out the life she has. “Others have not been so lucky. Some people never got over what happened to them,” she says, adding that one friend from her orphanage days still has nightmares about her experience. Fiona says that the children from the orphanage weren’t encouraged to keep in touch with each other when they left. “We were never told where people had gone although as the years have gone by, I’ve made contact with more and more people who were at the orphanage.” Fiona began investigations to discover who her mother was about ten years ago. After an exhaustive search she found out that she had a brother. He too had spent his childhood in an institution. “He was in Artane and was terribly abused.” Her brother had also sought escape from his past in England and lives in London. The two are in regular contact and Fiona says he was delighted that she had found out information on where they came from.

While her anger at what happened to them is still raw, she welcomes the fact people are at last beginning to realise what happened in institutions such as St. Joseph’s. “No one knew what was going on - it stopped at the four walls,” she says. “I would like people to know of the horrific abuse which occurred and that it could never happen again. The Nuns were being paid to look after us yet what happened was child abuse - if it happened nowadays they would be prosecuted.”

She accepts that not all the nuns were guilty of abuse. “There were three or four nice nuns, but they were in the minority.” Fiona says that while the children grew accustomed to the physical abuse, they never forgot the emotional abuse. I was told from a very early age that my mother was a dirty woman and that’s why I was in the orphanage. We were the product of sex, we were evil,” she recalls. “The Nuns were supposed to be helping society, and should not have been frowning on anyone or abusing children. We were the victims but they made us feel like they were doing us a favour. They gave us no love, care or attention.”

As acknowledged by a representative of the Mercy order at the public inquiry, St. Joseph’s orphanage was an unsuitable building for children, with inadequate heating. Fiona has abiding memories of the children being sent outside in all weather, even the depths of winter. “Our clothing was totally inadequate and we would huddle together for warmth and then if the nuns saw you huddling up against a colleague, you’d get a wallop.” Even when they went to school in Realt na Mara, Fiona says the children from the orphanage were treated differently, and were “systematically picked on and beaten by most of the nuns. I can vividly recall some of the other children asking me ‘why do they keep on beating you?’ Those of us who were illegitimate got a rougher deal as the nuns were fully aware that we had no one to turn to. Yes, we took it all and said nothing, but who could we have told, who would listen to us, we were the nobodies of society.”

Fiona says her only good memories from childhood are of being taken out twice a year by local organisations. “They treated us as children and with kindness.”

She admits that things started to change slowly for the better when she was around fourteen, but by then her self-esteem was low and she had an inbuilt fear and mistrust of anyone in authority. “However, my two years at the Technical School were a safe haven during the day from the physical and emotional abuse.” When she turned sixteen, she had to leave the orphanage and went first to Dublin and then to London. “A lot of girls would have gone to work on farms, but I knew I didn’t want that as I had done enough rubbing and scrubbing and slavery in the orphanage. When I left Dundalk, I didn’t know where I was going or what I was going to do. I had no education, didn’t know the value of money and had no social skills.”

She has found that the best way to survive what she had experienced was to put it behind her, not to think about it. “When I was younger I wouldn’t let anyone know where I was from. I had no sense of identity, had no mother or father, brother or sisters, so I told lies, lots of lies, as I didn’t want to be humiliated ever again.” Fiona was determined to take control of her life from then on. “I had to strive and strive. I worked very very hard for what I got.” She qualified as a nurse, got married and raised a family. “I don’t want to live in the past. I’ve tried to put it behind me and I hope I have peace of mind.” She is, she believes, lucky to have carved out the life she has. “Others have not been so lucky. Some people never got over what happened to them,” she says, adding that one friend from her orphanage days still has nightmares about her experience. Fiona says that the children from the orphanage weren’t encouraged to keep in touch with each other when they left. “We were never told where people had gone although as the years have gone by, I’ve made contact with more and more people who were at the orphanage.” Fiona began investigations to discover who her mother was about ten years ago. After an exhaustive search she found out that she had a brother. He too had spent his childhood in an institution. “He was in Artane and was terribly abused.” Her brother had also sought escape from his past in England and lives in London. The two are in regular contact and Fiona says he was delighted that she had found out information on where they came from.

While her anger at what happened to them is still raw, she welcomes the fact people are at last beginning to realise what happened in institutions such as St. Joseph’s. “No one knew what was going on - it stopped at the four walls,” she says. “I would like people to know of the horrific abuse which occurred and that it could never happen again. The Nuns were being paid to look after us yet what happened was child abuse - if it happened nowadays they would be prosecuted.”

Evidence sheds a chink of light

The Sisters of Mercy have apologised to the children who were in their care at St. Joseph’s Industrial School, Seatown Place, Dundalk, until its closure in 1983. In her evidence to the Commission to Inquire into Child Abuse, Sr Ann Marie McQuaid, Provincial leader of the Sisters of Mercy of the Northern Province of Ireland, said she wholeheartedly apologised “to any former resident of St. Joseph’s who experienced physical and emotional pain or damage while in their care.” Her evidence shed a chink of light on how the orphanage was run from its foundation in 1881 to its closure in 1983. There were seven children enrolled when it opened and by 1953 this had increased to 100. From the 1950’s the numbers decreased significantly and was down to 45 by 1956. There was an average of 30 children there in the 1960’s, but figures increased again when young boys were taken in 1965. The numbers slowly dropped and there were just three girls there when it finally closed. Sr McQuaid said that the documents or certificates which came with the children when they were admitted indicated that they were placed in the orphanage “because of poverty or poor social conditions, a parent had died, more likely a mother, and sometimes it was a parent who just wasn’t able to look after them.”

As the years progressed, policies on childcare changed, and more children were placed in foster homes, leading to a decrease in the numbers admitted to the orphanage. The orphanage building was not at all suitable for housing young children, she admitted, and the Order had received inadequate State funding for children’s care and capital expenses, particularly during the depression years of the 1940’s and 1950’s. This had exercerbated the situation had made daily life more austere for the children. “It was only in the latter period of the school’s life in the 1970’s with a smaller number of children and greater understanding of their needs that a more homely and intimate atmosphere could be created and the needs and attention of individual children could be given attention. Without a doubt we recognise that the system of institutional life in St. Joseph’s Industrial School was not an appropriate means of meeting the emotional and psychological needs of vulnerable and displaced children, neither was it able to meet their comprehensive educational needs and we deeply regret this.”

She described the orphanage as being a cold building, cold even after the installation of central heating, with long corridors, a basement and an attic “so it was a very formidable building for little children who were already traumatised to suddenly arrive in.” “St. Joseph’s building, while able to provide much needed accommodation, was an unsuitable and generally uncomfortable building for the children. It was limited in its potential for adaptation for more enlightened child care practices and it was inadequate in its recreation facilities. Even when much more effort was made to make it more comfortable, attractive and child friendly, it still remained very institutional in nature.” She said that other factors militated against providing children with the environment in which they could develop their full potential. One was the sheer numbers of children of such a wide age range and carrying so much inner pain, living together for most of this period with staff, who through no fault of their own, did not have professional child care training and only a limited understanding of the children’s needs. “The situation led to a highly regulated way of life where freedom was very restricted, conformity was the norm, privacy was lacking, discipline at times could be harsh and the needs of the individual child were often overshadowed by the group.”

She noted that of the 35 general inspection reports, only two, from 1944 and 1946, were negative. In 1944, the Inspector, Dr McCabe, complained that the children looked dirty and unkempt and that they had lice, and she also noticed that a couple of the children were underweight. Two years later, while noting that the children looked well fed and had put on weight, she was critical of what she called the careless and slipshod way in which the school was being run. She was particularly concerned about children under six who looked dirty and not properly washed. Sr McQuaid commented that the doctor had seemed really, really angry and this came across in her report. However, she pointed out that from the next year on there was a marked improvement in care, extra staff and a nurse came in, the situation improved and right up until it closed, the reports were positive. She said that while she acknowledged that the reports of 1944 and 1946 were critical, and the Order deeply regretted them, at the same time the school was described as being a text-book example of people playing a more important role rather than the buildings, as having a kindly and intimate atmosphere and with child care practices that were geared towards the interests of the children. “Sadly no institution, even if perfect, could ever recreate what a loving home offers a child or even substitute for the love of parents, particularly for vulnerable and traumatised children who were frightened and lonely and had already suffered so much and lost so much.” Questioned as to whether children in the Industrial School were punished, Sr M McQuaid referred to punishment books, but she said some of the records were missing.

Most of the punishment, it seemed to her, consisted of girls missing out on treats such as going up town, to the seaside or being made sit with the juniors. She agreed that there was also corporal punishment and this was usually administered by the Resident Manager or her assistant. This, she believed would have consisted of slapping. “I know from the last two Resident Managers that they would have been insisting that any slapping that had to be done or corporal punishment they would do it, but I would say that wasn’t always adhered to.” Asked about complaints by former residents that certain lay members of staff and nuns had treated them harshly she commented that “knowing human nature and knowing the length of time and the number of children, I think it would be unrealistic to say that there weren’t times when a child could have been treated harshly, We deeply regret it if we caused it and we deeply regret it if we didn’t notice it.” From her research, she gathered that “the policy was not to slap children who had bed-wetting problems but I would say there were times probably when they were slapped. Again that is something we would regret.” The lack of hot water for washing had been another problem in the Orphanage, with the water being boiled in the kitchen in the days before heating was installed.

Children at the orphanage attended the national school which was also run by the Sisters of Mercy. In the early years, it was in the same complex, and was later replaced by Realt na Mara. Sr McQuaid agreed that some of the former residents had made complaints about their education. “We recognise this and understand that the full potential of many of the children in the school was not realised and that this has caused great suffering.” She also accepted that many of the children would have had special needs and these would not have been met. Children at St. Joseph’s would have had more access to the town centre than those in other Industrial schools. Older girls would have had permission to go on messages and to bring younger ones with them. In addition, she said, “the people of Dundalk seemed to have embraced the children because there was tremendous interaction, there was a lot of support and care from the people of Dundalk for the children right through the 100 years including a whole god-parenting programme.” She also understood that the people of Dundalk, the parish, had actually bought a house at the seaside and they gave it to the children for the use of a month and that there was a committee which looked after that to ensure that the children had a holiday.

Some children would have had visits from family members, particularly if they were children who were put in the orphanage voluntarily by a family and maybe a mother had died and the father would visit and others would have gone on home leave as well. Sr McQuaid said that there was a three month preparation programme for girls about to leave the orphanage, and that they got a case of clothes and other things which they would have needed for moving out. She said that quite a number of them kept in touch with the nuns after leaving and even after St. Joseph’s had closed down. She had seen letters from former residents, as well as photographs of their weddings, of their children being baptised to which sisters would have been invited as well. She said that those who had gone abroad very often came back during the summer and there was always a place for them if they needed somewhere to stay. “That contact was very strong,” she said. “Sadly, since ‘Dear Daughter’ actually, and the beginning of the complaints, it has been sad that the contacts aren’t as strong.” Sr McQuaid also revealed that the first the Order became aware that former residents were carrying painful memories of their time in St. Joseph’s was following the book ‘Suffer Little Children’, in which a former resident gave her memories. “It was a grave shock to the sisters who had kept contact with a number of residents and were totally unaware that some were carrying those painful memories.”

SOURCE THE ARGUS (Dundalk)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)